By: Naraya Lamart and Ollie van der Zee

At a glance

- Decommissioning is a necessary and planned stage in the life of every offshore petroleum project, requiring consideration from the outset and ongoing development throughout the project’s life.

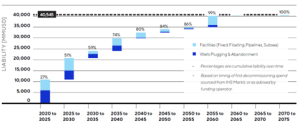

- Over the next 50 years, Australia is expected to see USD40.5 billion in offshore decommissioning activity, primarily focused on well plugging and abandonment, as well as pipeline removal.

- Titleholders are legally responsible for the full cost and safe removal of offshore infrastructure under the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006, and must meet strict environmental and consultation obligations.

Introduction

“Decommissioning involves the timely, safe, and environmentally responsible removal of, or otherwise satisfactorily dealing with, infrastructure from the offshore area that was previously used to support oil and gas operations. Decommissioning is a normal and inevitable stage in the lifetime of an offshore petroleum project that should be planned from the outset and matured throughout the life of operations”.1

Over the next 50 years, the Centre of Decommissioning Australia (CODA) estimates that USD40.5 billion2 of offshore decommissioning work will need to be undertaken in Australia, with well plugging and abandonment along with pipeline removal comprising the majority of the estimated spend.

In Commonwealth waters, the regulatory regime for offshore petroleum production and titleholders.3 is the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 (Cth) (2006 Act). The 2006 Act makes clear that titleholders are responsible for the full costs and safe removal of offshore oil and gas infrastructure. Titleholders must comply with a stringent environmental and safety approval process for their decommissioning activities, including thorough consultation with impacted communities.

While this signals significant economic opportunities for the broader Australian maritime sector, in an era when much greater focus and emphasis is placed on the green economy, decarbonising, and prioritising environmentally sound practices over economic expediency, it also raises questions over:

- the technical feasibility of carrying out these operations, and

- what the decommissioning and environmental obligations are for operators and infrastructure owners.

Why all the fuss?

The media has recently focussed on some high profile examples, such as Esso’s decommissioning plan for 12 platforms in the Bass Strait, Victoria, with the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA) raising concerns that not all of the infrastructure will be removed.4 The discussion around Esso’s proposal has generated debate as to what the 2006 Act permits.

While decommissioning activities under the 2006 Act cannot commence without the titleholders securing a series of environmental approvals through the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA), Esso’s decommissioning proposal includes leaving rigs in place and converting these into artificial reefs. This was previously done in the Gulf of Mexico.

The practice of leaving some infrastructure in place has created debate about the environmental implications and whether that breaches the obligation to remove under the 2006 Act (which is a strict liability provision). In October 2023, Professor Soliman Hunter, a leading academic in the field and Director of CENRIT5 published a report6 into best practice for dismantling, recycling, and disposal of offshore petroleum structures. The report provided key recommendations, including that Offshore Decommissioning Guidelines prepared by the Commonwealth’s Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources7 be amended to reflect the strict legal position articulated in s572 of the 2006 Act, rather than allowing abandonment in situ where environmental outcomes are equal or better than removal.

Subsequently, on 28 January 2025 NOPSEMA issued its updated policy for the maintenance and removal of property under s572 of the 2006 Act, along with an information paper for proactive decommissioning planning. In the paper8, NOPSEMA indicates that, notwithstanding that complete removal of all property is the “base case”, s572(7) does allow for alternatives where NOPSEMA gives a direction or the regulations provide an exception.

In relation to Esso’s proposal and what the 2006 Act permits, Professor Soliman Hunter has stated that Esso’s proposal is not permitted by the Act and believes that the proposal is motivated by reducing costs rather than environmental considerations.

Esso’s statement in response is that to completely remove the structures would involve undertaking significant dredging of the sea floor, which would involve not only removal of ecosystems but would significantly impact surrounding marine life.

In the Ecological Society of America’s article “Environmental benefits of leaving offshore infrastructure in the ocean”9, a survey of 38 experts suggested that partial removal options for platforms were considered to deliver better environmental outcomes than complete removal. Key considerations identified for decommissioning were biodiversity enhancement, provision of reef habitat, and protection from bottom trawling, all of which the article states are potentially damaged by complete removal.

As will be evident from only the little discussion above, decommissioning involves a range of complex and sometimes controversial issues. The purpose of this article is to provide a broad overview of the decommissioning players and regulatory framework in Australia, with further articles delving into a more detailed analysis of what the obligations and risks are for each of the players within the framework.

Australia’s international obligations

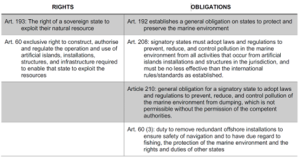

Australia is a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1994 (UNCLOS)10, which is the primary International legal instrument governing decommissioning.

A table briefly setting out some of Australia’s key rights and obligations under UNCLOS is set out below:

As can be seen from the above, a key corollary to the right of states to exploit their natural resources and develop infrastructure for that purpose, is their obligations to protect the marine environment and maintain safety of navigation.

The Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter 197211 (commonly known as the London Convention) covers the deliberate disposal at sea of waste, which applies not only to offshore support vessels but platforms and man-made structures as well.

Each of the above conventions has the force of law in Australia as they have been incorporated into our domestic legislation. As noted above, however, the legislation which specifically governs decommissioning offshore installations is the 2006 Act.

Subsidiary legislation to the 2006 Act12 implements the International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation (OPRC), which requires vessels to carry a shipboard oil pollution emergency plan and to report incidents of pollution to coastal authorities.

Finally, IMO Resolution A.672 Guidelines and Standards for the Removal of Offshore Installations and Structures on The Continental Shelf and in the Exclusive Economic Zone (Guidelines) establishes a general requirement, the best outcome under the Guidelines requiring:

- all installations weighing less than 4000 tons in air, standing in waters less than 75 m depth be completely removed, and

- installations which intrude upon shipping lanes to be removed in their entirety.

The stakeholders

As noted above, the 2006 Act is the primary regulatory regime that applies to decommissioning by titleholders in Commonwealth waters.

Under the 2006 Act, titleholders are required to decommission installations to the “base case” standard. This means the default decommissioning requirement is to remove all property and plug wells in line with the provisions of s572 of the 2006 Act.13

For the purpose of maintenance and removal of property, titleholders are defined in s572(1) of the 2006 Act as:

NOPSEMA has to approve all decommissioning activities under the 2006 Act. Titleholders have to engage with multiple and varied parties to meet their obligations under the 2006 Act and obtain NOPSEMA’s approval for decommissioning, including:

- heavy lift operators (both midsized and super heavy lift vessels),

- offshore support vessels (OSVs),

- tugs and barges to ship the offshore installation’s dismantled parts and equipment.

The relationships between titleholders and each of those players within the shipping industry are governed by different contractual documents (often BIMCO Forms) and liability regimes. It is important for the parties to be aware of their obligations and risks under each of these documents.

For example, semi-submersible vessels are used to transport offshore drilling rigs, oil production platforms, FPSOs, all types of foundations for offshore wind farms and other exceptionally heavy cargoes.14 A go-to contract in that context is the HEAVYCON 2007 Form, which is a “knock-for-knock” contract designed for the super heavy lift market. Those sorts of cargoes are almost exclusively carried on deck and are, in most cases, sole cargoes. Under this form a titleholder effectively agrees that it will absorb any damage to its property or personnel without pursuing any recourse action against the heavy lift vessel, regardless of fault.

However, for dismantled parts and equipment (Cargo) carried on midsized heavy lift vessels the conventional cargo liability regime of the Hague/Hague-Visby Rules is generally more suitable. In those instances, the HEAVYLIFTVOY Form might be more suitable, but the parties will need to turn their minds to whether the Cargo it is to be loaded free of risk to the vessel, and what the consequences are if swell or other environmental factors prevent or delay loading. Titleholders need to be across the liability risks for each type of Form and what this means in terms of not only damage to Cargo, but the circumstances in which demurrage accrues.

Barge transportation might also be required, not just for transport but also for floating storage of heavy and voluminous cargoes, such as modules for offshore platforms. This effectively requires a combined service involving the provision of a tug and a barge as part for transportation but also encompasses the carriage of goods. Does the titleholder contract separately for the hire of the tug on the TOWCON or TOWHIRE Forms, the BARGEHIRE Form for the barge, with Hague/Hague-Visby Rules to govern the carriage of the Cargo? Or perhaps it is more suitable to use the PROJECTCON Form, designed to cover the contractual requirements of providing a tug and barge for the carriage of a project cargo.

Finally, OSVs support offshore installations with operational needs, such as carrying goods, supplies, offshore workers, and equipment to and from the installation, in addition to assisting with building and repairing offshore equipment. A popular contract in the OSV sector is the SUPPLYTIME Form, which employs a knock-for-knock liability regime.

Taking into account the potential for pollution accidentally escaping from Cargo carried on board vessels, it is imperative that titleholders account for this, the liability implications for it and its contractors, whether this is dealt with in the Forms discussed above, or whether separate, bespoke rider clauses need to be tailored for the specific project.

What’s next?

Complying with regulatory requirements for decommissioning is far from the straightforward, aside from which decommissioning plans are likely to be subject to significant public scrutiny and reputational risks. It’s therefore crucial to develop an appropriate strategy with appropriate stakeholders, align this with insurance cover, and coordinate execution of this plan with logistic and supply chain suppliers.

In our decommissioning series, we will tease out some of the issues for the various contracts and identify key issues for each of the stakeholders referred to above.

Stay up to date on Marine & Transport

Complete the form below to subscribe to Wotton Kearney’s Marine & Transport updates.

[1] https://www.nopsema.gov.au/offshore-industry/decommissioning.

[2] Centre of Decommissioning Australia – https://www.decommissioning.org.au.

[3] Oil and gas producers hold a title in offshore areas.

[4] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-07-12/controversy-over-essos-plans-to-dismantle-offshore-gas-rigs/104076538.

[5] Centre for Energy and Natural Resources Innovation and Transformation.

[6] https://www.mua.org.au/sites/mua.org.au/files/Report%20-%20Best%20Practice%20Regulatory%20Reform%20Plugging%20and%20Permanent%20Abandonment%20of%20Offshore%20Petroleum%20Wells%20-%20August%202024.pdf.

[7] https://www.nopta.gov.au/_documents/guidelines/decommissioning-guideline.pdf.

[8] https://www.nopsema.gov.au/offshore-industry/decommissioning

[9] Front Ecol Environ 2018; doi: 10.1002/fee.1827

[10] Australia primarily fulfils its international obligations under UNCLOS through the Seas and Submerged Lands Act 1973 (Cth), but also through the 2006 Act, and Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).

[11] Australia fulfils its international obligations under the London Convention through the Environment Protection (Sea Dumping) Act 1981

[12] https://www.nopsema.gov.au/offshore-industry/environmental-management/oil-pollution-risk-management

[13] https://www.nopta.gov.au/_documents/guidelines/Offshore-Petroleum-Decommissioning-guideline.pdf

[14] https://boskalis.com/about-us/fleet-and-equipment/offshore-vessels/semi-submersible-heavy-transport-vessels